With a heart of furious fancies,

Whereof I am commander,

With a burning spear and a horse of air,

To the wilderness I wander.

---Tom O'Bedlam's Song.

As quoted in E.A. Poe’s The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfall (1835).

If you didn’t feel like leaping onto a horse of air and wandering into the wilderness this week-month-years—I don’t know what your life is like. But here, that’s what’s going on.

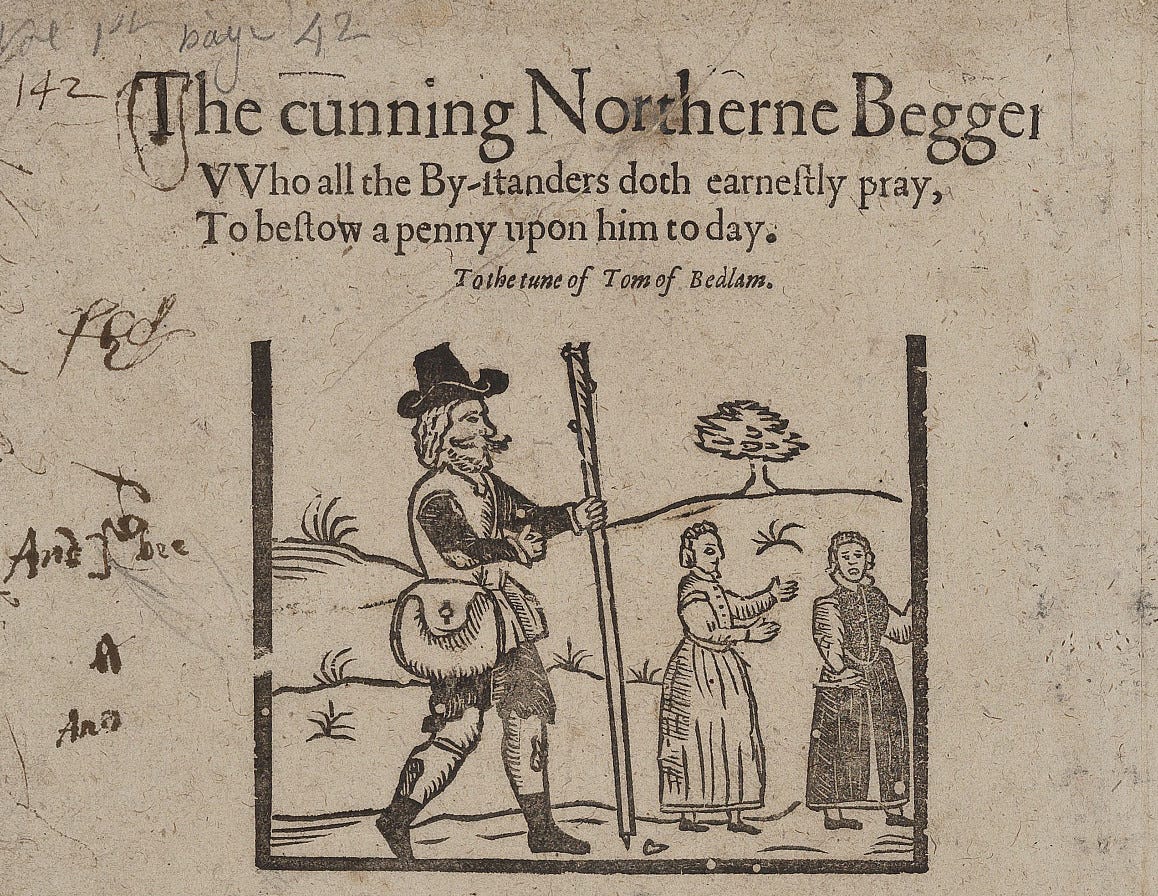

Tom O’Bedlam’s Song is an anonymous English poem from around 1620 in which a madman sings about his story, encounters, his fearlessness, imagination, his life as said madman; meandering through the wide wild world. Each verse is interspersed with an appeal begging women and girls for food, drink or clothing. He owns his heart, his imagination, and a horse of air. Poe’s italics point us to the flight of fancy he’s introducing, a balloon adventure all the way to the moon.

I never paid attention to this initial verse until yesterday when I started compiling introductions and dedications and correspondence from the things I’ve been reading.

I’ve been thinking about dedications as letters to both present and future: immediate audience addressed; hoped-for audience, imagined.

Poe dedicates his last piece of writing to Alexander von Humboldt, explorer, cataloguer, scientist, observer, who attempted to understand a certain kind of science and culture together as one Cosmos. Their philosophies intertwined despite the age, distance and vast reputational & status differences between them. Poe died in 1849 at 40. Humboldt in 1859 at the age of 89.

Poe’s Eureka dedication page is simple:

WITH VERY PROFOUND RESPECT

This work is Dedicated to

ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT.

The following page contains what Poe calls a Preface, but it too is a dedication, written in a personal, plaintive, insistent tone. In it, Poe addresses a handful of people, real and imagined, people he hopes will understand and accept what he is saying. This dedication, unlike the first of respect, offers truth in the form of poetry, and asks for love, understanding, compassion, and the suspension of disbelief:

To the few who love me and whom I love -- to those who feel rather than to those who think -- to the dreamers and those who put faith in dreams as in the only realities -- I offer this Book of Truths, not in its character of Truth-Teller, but for the Beauty that abounds in its Truth; constituting it true. To these I present the composition as an Art-Product alone:- let us say as a Romance; or, if I be not urging too lofty a claim, as a Poem.

What I here propound is true:- * therefore it cannot die:- or if by any means it be now trodden down so that it die, it will "rise again to the Life Everlasting."

Nevertheless it is as a Poem only that I wish this work to be judged after I am dead.

Thomas Baldwin, the 18th century English aeronaut, dedicates his descriptive and instructional Airopaidia (1786) to townspeople who helped keep things working smoothly on his big trip. But he omits his name, giving himself a title of aironaut, and in so doing, makes himself a category rather than a person. He is lighter than air and larger than life, even as his balloon rises out of sight:

To the Principal Inhabitants of Chester

For their polite attention on the day of ascent, and preservation of order during the inflation: on which, the success of aerial experiments so much depends, and through the want of which, so many have already failed; for the kind anxiety manifested during his absence; and for their friendly congratulations, on his safe return; the following account of the balloon-excursion, written at their request, is, by their permission, with all gratitude, esteem and respect,

Dedicated

by their most obliged, and most obedient servant, THE AIRONAUT.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the Taylor Swift of 18th century aeronauts, claims simplicity and truth as his primary goals, in keeping with his self-understanding as a man of science, of adventure, of the now. In the dedication from his 1793 ascent and flight from Philadelphia to New Jersey, the first such balloon adventure in the brand new United States, he flatters the big boss and asks the rest of us a favor:

Inscribed

To George Washington, President of the United States of America, The Patron of Liberty, the Laws, and the Fine Arts, by his most humble and most obedient servant, Blanchard

And here I request the indulgence of my readers for the style of my narrative--Elegance is not what I am at in this performance: Truth is intended as its sole ornament.

Each writes a letter to the present and the future. Each claims to speak the truth. But the truth is a lot more like Tom O’Bedlam’s song, wending and winding, swinging in the wind between fact and fiction, as all letters do.

In my previous projects about what I call long sleepers, I became fascinated with writing that pretends to be sourced from letters or notes found by chance. This framing as discovery allows the author to jump in and out of time and space. It muddles notions of fiction and truth.

On a flight the other day, I finished reading an essay called “Found among the Papers: Fictions of Textual Discovery in Early America,” published in Early American Literature, Vol 56, Number 3, 2021. The essay is by Lindsay DiCuirci and was just what I had been looking for.

Much like finding scraps in a drawer, my infrequent JSTOR searches allow me to throw a bunch of PDFs on a computer and read them in bursts, usually when traveling. This one described the phenomenon I had gleaned from my own textual wanderings and added some new ways (for me) of understanding what this 18th & 19th century trend in American literature was about.

So-called “found” documents let an author self-fictionalize. They also enabled the production of an archival imaginary in a country that was, in the late 18th century, starting a fevered catch-up process to write its own narrative of formation.

“Found” papers or documents meant there was an earlier (white) America to learn from. The “found” story creates an archive of the presence of a particular people in a landscape no matter when they arrived. It allows a contested place to be consolidated; owned. Scraps and bits imply there is a whole and the work is to piece that whole together.

This is useful. But in my (desired) reading, “found” messages and unfinished manuscripts also provide great cover for an experimental narrative. Even better if the “true” author has disappeared into a whirlpool or a mist. Scenes can happen in any order because they were found in a drawer all scattered: we’re just telling it like we found it. We can’t know the whole because there has never been one.

A dear friend reminded me recently that one of my earliest installations and obsessions was with an object, a space, a thing called a genizah. A hidden place in the ceiling filled with scraps, of trash mixed with bits deemed sacred. And you could never reconstruct it completely. For a show in graduate school I asked an acquaintance to build me a fake ceiling out of an old chicken coop he brought back from Kentucky. I filled it up with a bunch of torn and folded papers, the contents of which I cannot recall. Even though nobody could see what was inside, it seemed important to fill it completely.

I hung the false wooden ceiling from the gallery ceiling. On the other side of the room I built a wall and drilled peepholes at different levels. Behind the wall a 16mm projector ran a hand-processed film loop of moody allusions to Walter Benjamin’s now-legendary lost suitcase of notes and documents. The point of the peepholes in the wall was that you could never see the whole film; you always were missing something.

Shelves along the opposite wall held handmade magic lantern slides containing images from the film. I insisted the gallery workers light real candles on each shelf every day. The candlelight projected a faint, wavering image on the wall.

During the show, if I visited the gallery and as often was the case I saw a candle burned out or the film loop broken I would become irate or despondent. Needless to say I spent a lot of time there, fixing things. I kept the false ceiling as a bookshelf for another year and threw it away when moving from Chicago to New York.

Later, when I started making text animations I used more fragments, my receipts of trying to live on $5 a day in New York together with re-drawn illustrations from self-help books, musical phrases, or lists of inert ingredients. I felt satisfied in the presence of adjacencies. I put faith in my (mis)reading of Dziga Vertov, trying to get viewers to interpret new meanings by jamming disparate things together. In my case, those things are usually texts, which isn’t what Vertov meant at all. And it was Vertov’s wife and collaborator Elizaveta Svilova who was doing the actual, physical editing.

These days I struggle with the same questions, is allusion enough, adjacency, will the scraps expand the way I hope, to fill the heart of someone watching? I can’t bear the thought of having to tell everything, nor do I trust images to speak a thousand words.

You demand the letter reveal its secrets and, within that demand, you desire to get closer to whoever wrote it. Not even the author, in fact. You know the author is a cloak or a shell for your own desire to approach whatever impulses made that missive possible. The impulses that made those ideas, that writing, that film, that work of art come into being in a world where there was nothing before. That is correspondence. Bringing into being, through another medium, a cloud that hovers between you and the person, the past, the future. A cloud you both can meet inside.

Correspondence means you can escape yourself yet not lose yourself completely. As I have written many times before, notes tied and taped to strings of party balloons produced some of the most significant imaginations and connections of my childhood, inspiring a lifetime of reaching out to strangers for no practical reason. The letter back from an ancient farmer in West Virginia who found my letter in his cornfield, his letter to me was was an emblem of art’s potential.

You send something out in hopelessness and you get something back, and that something is not anything you made but something you prompted into being with surprise, curiosity, and a mutually shared power, the power to send, the power to receive, and to send back out again.

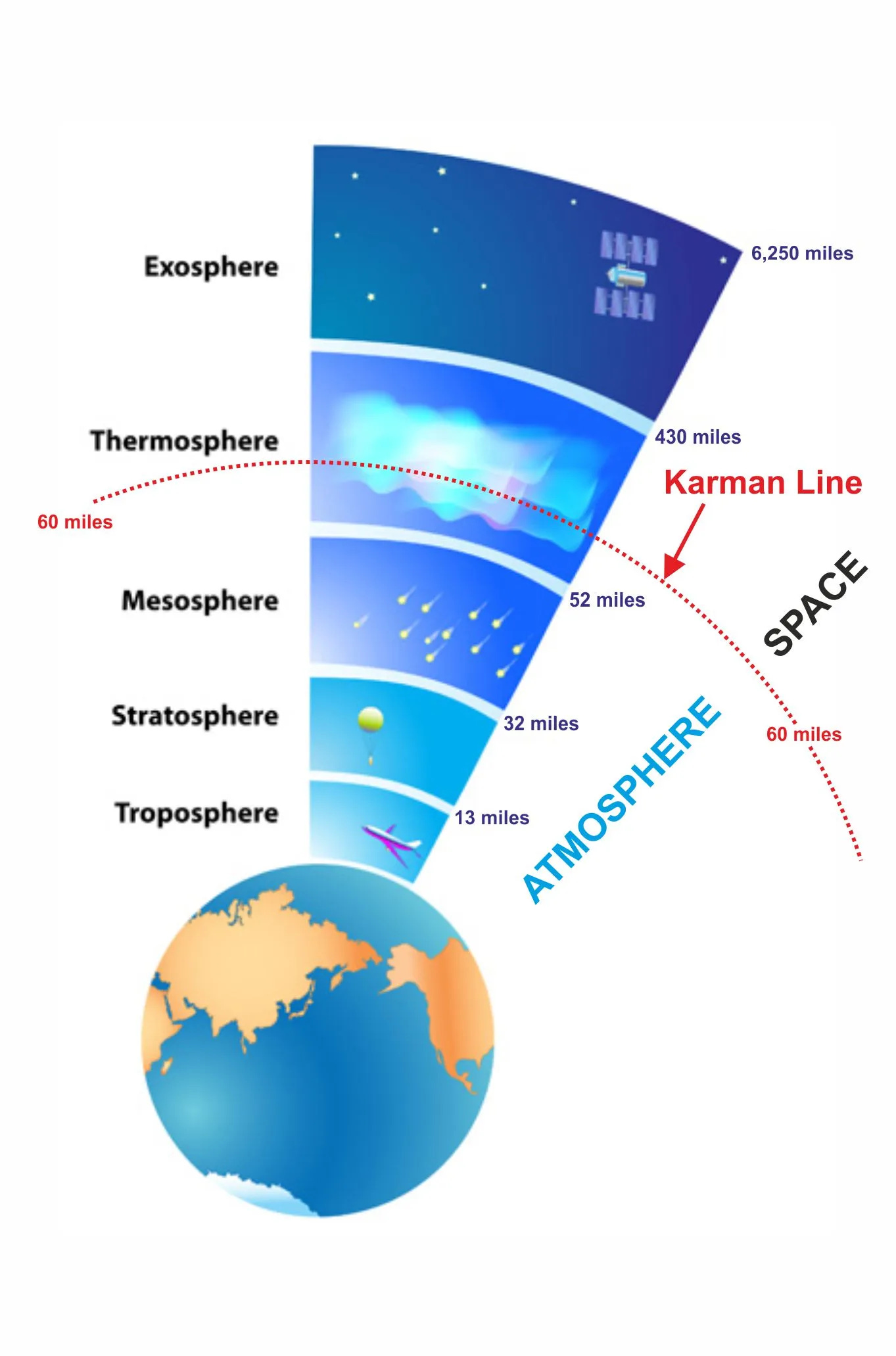

Last week I received an email from Armelle, the aerospace engineer with whom I’ve been in correpondence since 2021 when I sent an email to the info @ swedish space agency to ask if I could visit the Arctic space center to film balloon launches. Armelle wrote that she heard from a group of artists who want to put some things on a sounding rocket to send up to the Kármán line and asked if I wanted to be involved. Of course I said yes.

To the wilderness I wander.

Thanks for reading.

P.S. if you want to read the full Song of Tom O’Bedlam it’s here (with a bit o’commentary)

To watch my feature documentary BUNKER while preparing your own horse of air, find it on Amazon Prime, Mubi, Metrograph, and Projectr.tv.