Exceeding

the Limits of Credibility

I got back from Norway a week ago. On Sunday I took Emma to sleepaway camp in the Catskills and then drove straight down to Philadelphia. It was a long driving day. I had scheduled a drone shoot the following morning to approximate the liftoff and landing of Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s 1793 balloon flight. The first flight in the United States left from the courtyard of the Walnut Street Jail next to Independence Hall and landed 11 miles away in New Jersey.

After much searching I had found a small company willing to risk doing this unusual shoot. The FAA restricts a lot of airspace around Independence Hall but one guy, Nick, knew how to make it work. You just had to keep the drone on one side of Walnut and not cross over. It was fun to watch Nick make a robot dragonfly take off and disappear into the sky. To see what the drone saw I stood on my tiptoes and peeked over Nick’s shoulder as he moved the tiny joystick controllers. Apparently the FAA allows drones to fly 400 feet higher than top of the tallest building in the area, so up and more up it went to 700 feet. Up over the city, pointing downriver, then zipping back, emerging from nowhere and landing at our feet like an obedient insect.

After downtown Philadelphia we drove over to the Deptford Landing mall in New Jersey. I’d scoped it out on Google Earth and indeed I turned left at the mall entrance and took the winding road on the right hand side of the Walmart superstore and behind the loading dock and there, mere feet from the chain-link fence and forklifts and squashed bundles of cardboard was the glorious Clement Oak.

I’ve written about the Clement Oak before. To be in its presence was both painful and magical. According to recent online reports it was destroyed completely in 2021 by storms linked to climate change. And in fact the two days I was in the area there were huge storms, lots of downed trees and intense humidity—and two rainbows.

I guess after the 2021 storm nobody went to check. Most of the Clement Oak is dead, enormous limbs scattered around, covered in vines and fungi. The places where the branches once were are now open holes you can see through and lose yourself in. Perfect for all kinds of wildlife. But out of one large not-quite-dead limb was an enormous half-crown of large healthy branches overflowing with deep green oak leaves. The oak is coming back to life.

In front of the Clement Oak I felt a strong sense of humility and sadness and just a hint of hope.

The drone whizzed up into the sky and behind the tree, on the screen, me on tiptoes looking over Nick’s shoulder, I saw snaking small rivers joining with larger ones. I saw ponds and the last bits of woods. I saw the enormous highway blasting its way: a straight line ignoring soft curling ones. I saw the false curves of New Jersey suburbs, houses clustered along sidewalkless roads like raindrops on a spiderweb. And then the drone returned to the tree. I hardly heard it buzzing in to land. It felt nothing for its majestic subject, no respect, no emotion. But I did.

The Walmart workers watched us for a while and asked what we were doing but because the tree is landmarked and has a couple of overgrown plaques in front of it and the chain-link fence with the small faded balloon attached, we could answer clearly and point to the signs and they left us alone.

For a while there was a truck with a huge Old Tyme bread logo on it and I thought that was funny. After it left, the Little Debbie Snack Cake truck came and parked where the Old Tyme bread truck had been.

I kept thinking about what the tree sees and how calm it is, watching the workers and their forklifts and the cinderblock back of the Walmart day and night and I wondered how it must feel having owls and squirrels and snakes and bugs and fungi all over it. If it’s comfortable, or if it tickles.

I went into the Walmart and got distracted by pallets of mayonnaise and grotesque quantities of chips and Fourth of July charcoal. I got some water and came back out and filmed 16mm with the Bolex for a while. Normally I shoot with a fixed camera, stuck there on the tripod, but it didn’t feel right. So I roved around, winding the camera up, shooting, winding again. Some in black and white because I must have left it in the camera from god knows when, and then a roll of color. It was hard to leave.

Like with so much else I do, I have little desire to look over what I’ve made. I don’t plan to develop the film right away and I haven’t even opened one of the dozens of enormous video files the drone shot. For now, I prefer to jump myself over there in a less mediated way. I just think myself there and then I’m there. In the heat. Looking at the tree. It’s a comfort.

There is so much else I want to write now that I’ve started. About the following day’s trip to the Academy of Natural Sciences archive to see the collection of materials and the hollow earth globe of John Cleves Symmes, Jr. and the uncanniness I felt seeing that material from the 1820s from Butler County Ohio and all the names of the towns right near where I grew up. Of imagining what it must have looked like then. Of projecting into that time the whys and hows and wonderings of what motivated this guy, who had been a well-regarded captain during the 7 Years’ War, to spend the remainder of his years writing letters to everyone in Congress and all the newspapers and doing lectures and promoting his insistence, the truth of his theory and proof that the earth was hollow. And that his friend James McBride who was on the Hamilton Town Council believed him too. The whole Council endorsed Symmes’ ideas and put out a statement to say so. That McBride kept all the articles and handwritten lecture notes with meticulous copied drawings all in one now-fragile volume. And how Poe just grabbed that strange notion, whether he believed it or not, and wrote it into some of the greatest American literature ever made.

I’m still trying to make sense of it. Maybe that’s not possible.

Lately and often I am thinking of the poet Susan Howe onto whom I project an imaginary way of working, one that allows me to identify with her method, even if I don’t know her method at all. This imaginary way is a combination of instinctive archival meanderings and deep reading, thinking, and research into American history. Through the writers I love I give myself permission to work the way I do.

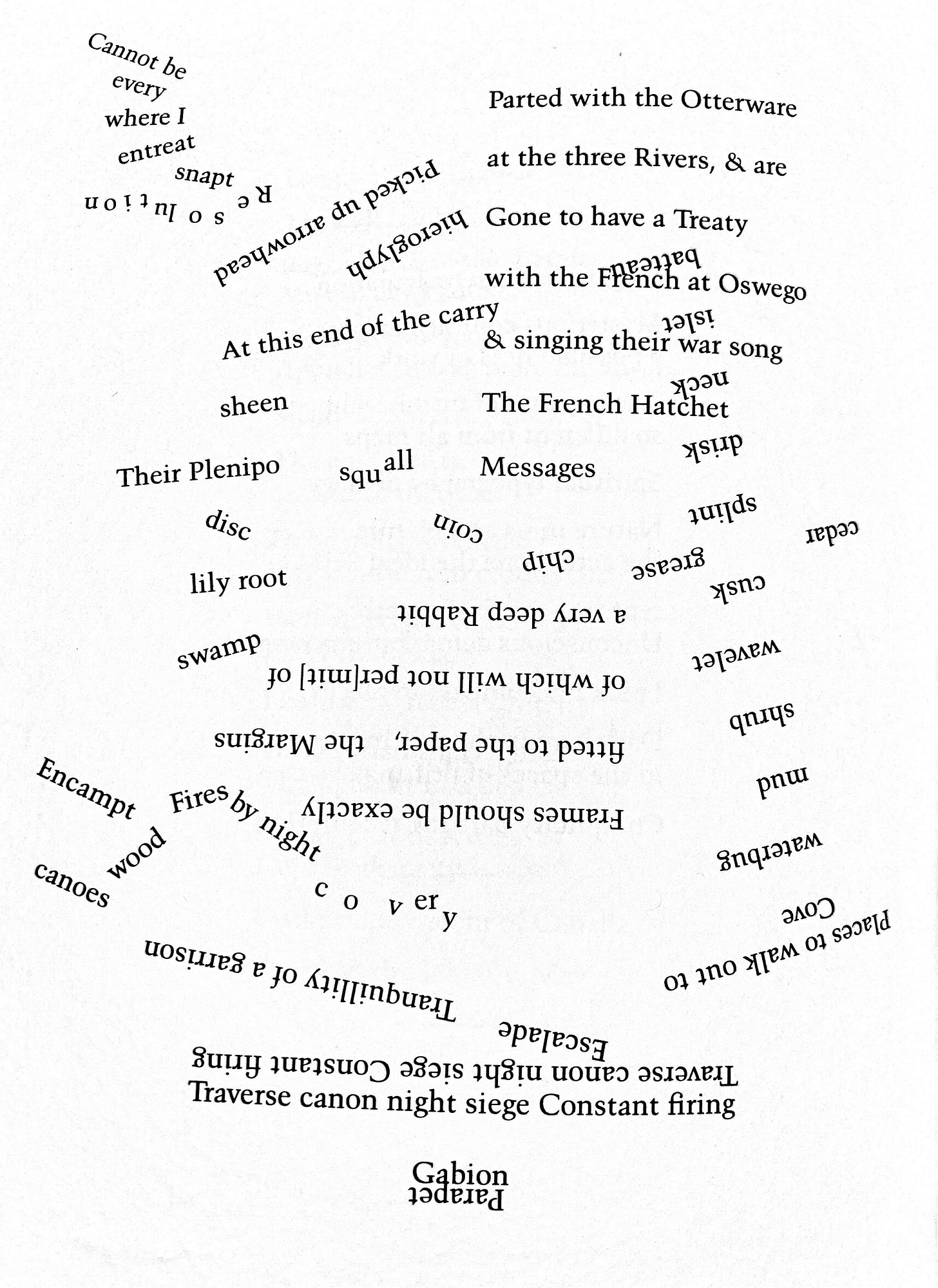

I’m wondering how to look at the failed American project, doomed from the get-go. What lens can I use to examine the crumbled bits, the salted soil. What stories the cast off, incomprehensible half-phrases, the messages of no import, might tell.

I like it when things don’t add up, and when I have to read through a forest of words, or puzzle at something that shifts as I look at it. I feel this when reading some of Howe’s writing. A similar pleasure arises when I look through the tangled mess of one of Lee Friedlander’s nature photographs. But Friedlander makes me laugh more.

And I keep thinking about William Carlos Williams’ “In the American Grain” which is another lodestar for me now. Also because it doesn’t fit what is “typical” for WCW. And because it was overlooked when it was published about 100 years ago. That book is brilliant, it made me gasp while reading. It was like being guided by an unknown hand to moments of clear-seeing, over and over again.

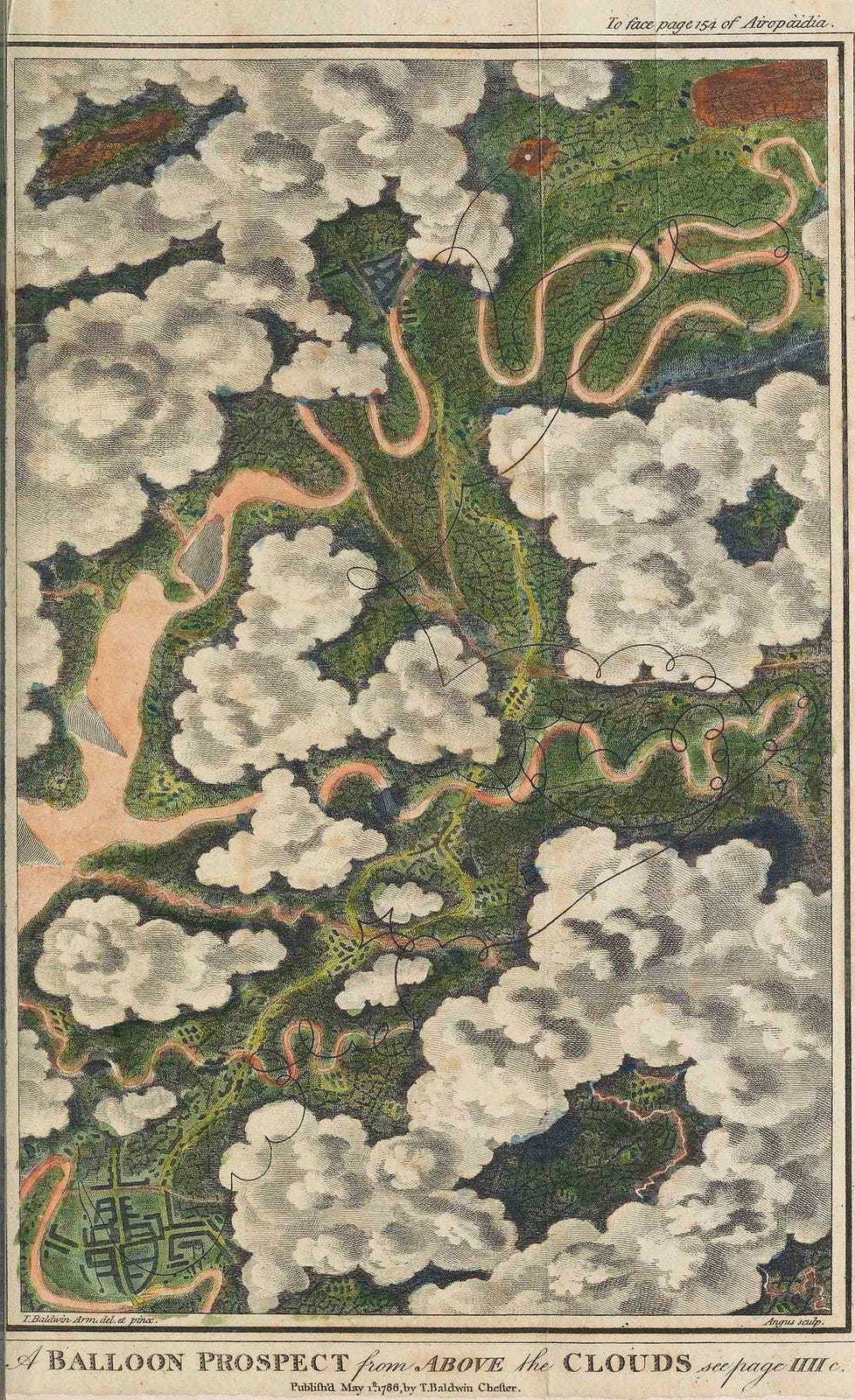

These experiences make me feel perhaps a bit like Thomas Baldwin did on his 1783 balloon flight in England as he was carried in and out of the clouds. The colors above, the variations of winds felt but not seen, the bright sun, the clouds below. As soon as you notice something, you begin to grasp it, it changes. And down below, all the way down, the snaking river and forest and small tracts of farms and villages might even resemble what my robot dragonfly got to see earlier this week.

Maybe it doesn’t all have to tie up together. I always believed in the messages that fragments convey. I need to remember that now.

Here are a couple of things from WCW and Howe for now.

Introduction from “In the American Grain,” by William Carlos Williams, first published in 1925:

“In these studies I have sought to re-name the things seen, now lost in chaos of borrowed titles, many of them inappropriate, under which the true character lies hid. In letters, in journals, reports of happenings I have recognized new contours suggested by old words so that new names were constituted. Thus, where I have found noteworthy stuff, bits of writing have been copied into the book for the taste of it. Everywhere I have tried to separate out from the original records some flavor of an actual peculiarity the character denoting shape which the unique force has given. Now it will be the configuration of a man like Washington, and now a report of the witchcraft trials verbatim, a story of a battle at sea—for the odd note there is in it, a letter by Franklin to prospective emigrants; it has been my wish to draw from every source one thing, the strange phosphorous of the life, nameless under an old misappellation.”

And from “Thorow,” by Susan Howe. Here’s her introduction of sorts, followed by one of the poems. The lack of punctuation at the end of these two paragraphs is intentional.

“During the winter and spring of 1987 I had a writer-in-residency grant to teach a poetry workshop once a week at the Lake George Arts Project, in the town of Lake George, New York. I rented a cabin off the road to Bolton Landing, at the edge of the lake. The town, or what is left of a town, is a travesty. Scores of two-star motels have been arbitrarily scrambled between gas stations and gift shops selling Indian trinkets, china jugs shaped like breasts with nipples for spouts, American flags in all shapes and sizes, and pornographic bumper-stickers. There are two Laundromats, the inevitable McDonald’s, a Howard Johnson, assorted discount leather outlets, video arcades, a miniature golf course, two run-down amusement parks, a fake fort where a real one once stood, a Dairy-Mart, a Donut-land, and a four-star Ramada Inn built over an ancient Indian burial ground. Everything graft, everything grafted. And what is left when spirits have fled from holy places? In winter the Simulacrum is closed for the season. I went there alone, and until I became friends with some of my students, I didn’t know anyone.

After I learned to keep out of town, and after the first panic of dislocation had subsided, I moved into the weather’s fluctuation. Let myself drift in the rise and fall of light and snow, re-reading re-tracing once-upon”

And one more, from Baldwin’s Airopaidia (1783). I picked a page at random; there’s so much more good stuff in there:

“At 47 Minutes after III, the Prospect beneath opened, just wide enough to shew, that he was suspended in the open Space over the Center of some Rivulet. The Map of the Country which ha been so carefully studied, was now consulted for the first Time, but coud not bring to his Recollection any Traces of the extraordinary Curves which then met his Eye. They bore not the least Resemblance to any Part of the River Mersey. No River like that below him had ever presented itself. Its Doublings were so various and fantastic as to exceed the Limits of Credibility.”

Thanks for reading.