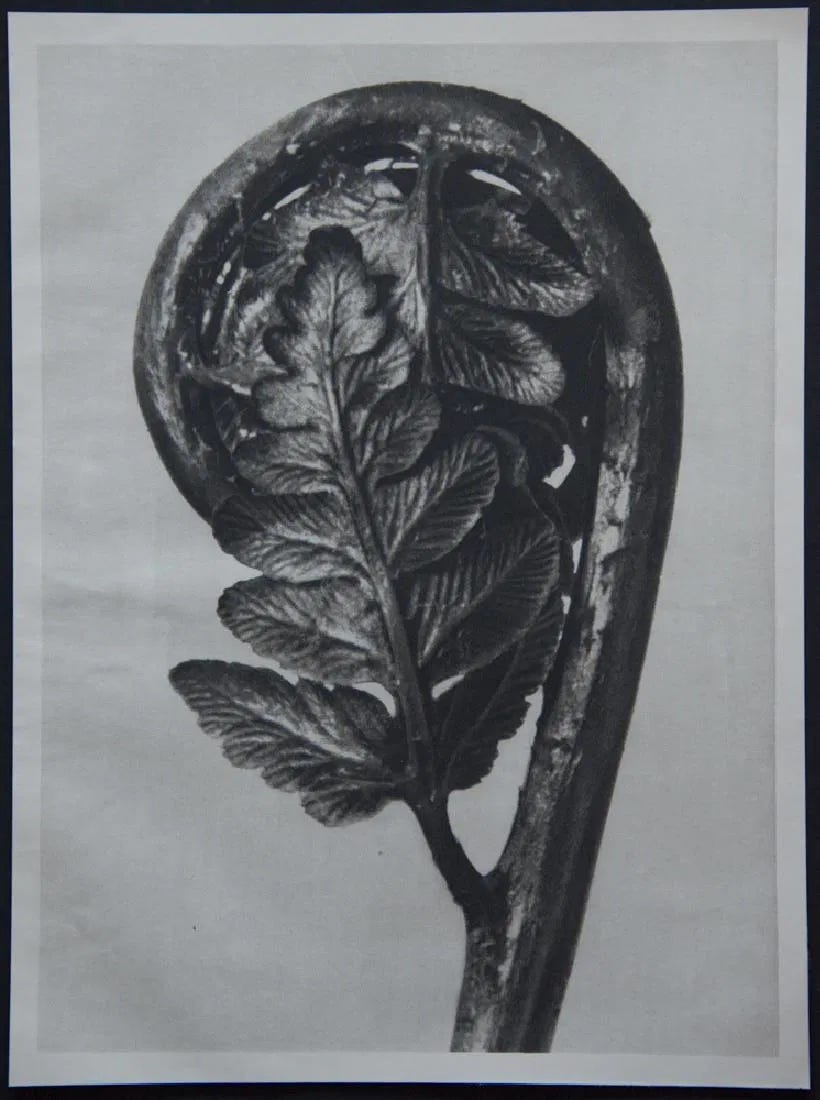

I’m a fiddlehead, I told a friend some years ago. She agreed.

There are a lot of other kinds of things I identify with but today I will think about fiddleheads, because they’re around. I saw them in the botanic garden and in the local grocery store. To prepare as food, fiddleheads have to be washed carefully and then cooked at a certain temperature so as not to poison those who ingest.

I love ferns and I like to think about their secret unfolding on their own time. They emerge from damp ground and don’t like too much sunshine. They come up all spiralled and when nobody is watching they uncurl, revealing wide-expanding detailed leaves. In the woods I often check under for the spores. I like to consider spores too, tiny circular mounds all lined up, full of more tiny circles that open up and float through invisible air currents to sprout new fiddleheads in a different forest place.

Another fern I love as much if not more than the typical one is the staghorn fern, because it’s an epiphyte; doesn’t require any soil at all to grow and can just hang out doing its thing, attached to another tree or in a basket or on a piece of wood or wherever. It gets its nutrients from the air. But it doesn’t have fiddleheads so it doesn’t quite match the awkward metaphor I’ve got going here.

As a child, when called upon to play a piece on the piano for family guests, I retreated into my room or somewhere not to be seen. Later, when nobody expected it, I would sneak into the room with the piano which was often adjacent to where the guests were, and I’d explode through a Mozart sonata or an extra-melodramatic Beethoven or a somewhat graceless but deeply felt Debussy. Then I’d sneak back out the door to avoid the guests again.

Maybe the verb for this is fiddleheading. But it’s not quite that. There are a couple other leaves from childhood. One, jewelweed, grew down by the creek and resisted; when dipped in the cool flow, the water glowed on its surface, silver, rolling, mercury-like. We did this again and again, pulling the leaf out of the water and acknowledging its regular green, dipping it back in and marveling at its extra-terrestrial shine. We tried to balance luminous drops on the leaf’s surface and roll them around until the wobbly liquid dropped back into its current.

The third leaf was a kind of thorny sticky one made up of many, kind of like a locust but in miniature. Before the internet I would not have bothered to look it up. Now I see it is called “sensitive plant,” among many other names. These transformed in a different fashion. A finger’s touch and the whole set automatically folded into itself and after a time would slowly open out again.

These phenomena surely had important functions in the natural world; we never tried to investigate further what those “proper” uses were. To us they were magic and a source of repetitive play, time unfurling under the maples and buckeyes and oaks. I would not say times were simpler then, because they weren’t. But a respite like that is what I often seek and find in different places even now. With writing, with music, with art, with people.

It has however been difficult to write in recent weeks and I hereby once again reiterate my commitment to this writing project, despite lapses. My current fiddleheading has been for a range of reasons, completing a voluminous text for the PhD, working with color correcting folks and sound mixers and kind image captioners to help me bring a lot of things together with the films and writing that I couldn’t do myself. This is ongoing, as I am leaving soon to go back to Oslo to install the final exhibition of this multi-year project.

It is hard for me to ask for help and I am very grateful to everyone who has been so generous with their time, energy, and skills. It’s astonishing to me that others believe there’s something worthwhile in bringing an exhibition of new work on an unusual subject into being. This is a gift I find it hard to fathom but have to trust.

There will be five films and one photograph in the show. The written part seems to have become a couple hundred pages long, constituted not only of many of these essays from the past few years but also contextual and research materials I hope can guide people through the questions and expressions I have explored.

I don’t like closure but when its necessity appears on the horizon I wrestle with feelings of contempt and dismissal about the works, the effort, the use of all of it. I am trying to hold those feelings at a distance right now. When I talk with my students about their works in progress I am overwhelmed by my own fierce belief in the importance and near-existential necessity of art. I am sure they are overwhelmed by me too. But in my own leaky rowboat of creative production I have to force myself even to lift the bucket to bail out the water. So that’s what’s happening.

When I think about ferns I think about Anna Atkins and I think about manias like balloonomania of the late 18th century. There was a fern mania too, in the 19th century and I always wonder what causes viral phenomena of one kind or another, not about people but about things.

I have no doubt many scholars have already done that work so I’ll just describe a little bit about fern mania, called Pteridomania, which emerged first in Britain. Women and men of different classes all found themselves stomping around in the damp, subdued light of the forests, which were more accessible because of the advent of railways and new roads. People were searching for these low-lying plants, pulling up so many specimens for their collections that many ferns became endangered species. New architectural structures called ferneries sprouted all over the place to replant the specimens in romantic grottoes. The mysterious fecundity was displaced and reinserted into steamy yet controlled spaces for further study and contemplation.

Connections between repressive Victorian manners and the uncontrollable spread of spores and various moist unfolding greenery are not to be overlooked here. The unstable ground of the forest. The parasols, long skirts, specimen baskets. The afternoons replanting cuttings or pressing leaves into books; tracing language of identification that could not describe the experience but merely marked a category.

At any rate, I just wanted to mention pteridomania. In part because I spent a lot of time thinking about balloonomania that overlapped in the 19th from its origins in the late 18th century. As always I wonder about how peoples’ desire to capture and make manifest uncontrollable forces like air, wind, growth, or narrative, results in all this building of artificial, technological objects like balloons and hothouses and systems of cataloguing that in themselves are technical, requiring specialized knowledge yet simultaneously presenting murky coalescences of myth, speculation, magic, belief, projection, and desire.

Obviously scholars like John Tresch or many others do a much better job of describing how all that goes, but as an artist I still value the special space I can occupy in wondering and wandering through. I suppose putting this exhibition on is a little like the pressing of experience into a representation of itself, made up of other incomplete expressions of lived time from the last few years. Maybe whatever unfurls in combining these works in the fernerie of the gallery can produce new spores to send out into the world.

There are a bunch more stories I want to tell but that’s enough for now. A short note to say that tomorrow is International Workers’ Day, aka May Day. But in the U.S. there is no official holiday. In this country Labor Day’s in September. You can intimate the historical and contemporary reasons for this change and its resulting effect that people in this country won’t have time to be in solidarity with workers around the world. But happy May Day.

May 1 is also the anniversary of the passing of my beloved Grandma Belle, born in 1908 and raised in a tenement on New York’s Lower East Side. She always had a smile to spare for everyone, day off or not. I’m grateful to have known her.

Thanks for reading.

More pteridomania here

More Blossfeldt here

And how to grow ferns from spores, in case you’re interested

There’s a lot in the news these days about prepping and bunkers, for obvious reasons. BUNKER is available for streaming on a range of sites including Amazon. It’s available for educational distribution and library acquisition through Grasshopper Film. And if you’d like an in-person director presentation you can contact me here.