Put your hand on the blue tape.

She puts her hands on my bare waist and guides me to the left. Step here. Elbow up. She lifts my arm with care, then slides her hand underneath my breast. Step forward. Get your belly in the picture. She adjusts my body part on the black plastic surface, centering it on a white square. She walks away. A humming sound and the 6-foot-tall machine I am standing in front of presses a clear plastic plate down. I turn to the left and see the woman and a colleague behind a plastic shield. One presses a button and an invisible beam I do not feel goes through me and makes my inside visible to them. They are now looking at the picture to make sure it is not blurry. I turn my head right and see an LED screen set vertically like a museum video installation with a smartphone aspect ratio. I see the black and a wild network of white squiggles and oval outline for a moment, the image of a foreign object, a part of my body, imaged on the other side of the room. The picture disappears from the screen. The woman comes back, presses a button to lift the plastic tray and then lifts my breast off the surface. Another button, the whole machine turns diagonally the other direction and the same. Put your hand on the blue tape. Step here. Move forward.

We will send the pictures to the radiologist and if anything is off we will send you a message. If everything is fine we will also send you a message. I should say here that there is nothing out of the ordinary here, this is a routine mammogram. I got it last week in Oslo by responding to a letter that said at my age a mammogram is recommended. The letter offered an appointment. I was in Oslo and curious about what going to get preventive care was like somewhere besides the U.S.. Somewhere that didn’t ask for your insurance number the moment you crossed the threshold. Somewhere that felt more trustworthy.

This is also the reason I went to my regular doctor here for the first time. The doctor was assigned to me by the city; I received his information in a letter and an email. It felt emotional to make an appointment where the person on the phone said what time and what day and not why, or do you have a referral, member number, group number, sorry, we’re out of network, you can submit a claim after payment after you meet the deductible. Surreal to arrive and greet a woman sitting behind a desk and hear her say have a seat without handing me a clipboard filled with photocopies and liability forms and health forms to fill in again like you did the last time and the time before.

After a short wait I enter the spare office, the doctor asks me so why are you here and I respond because I haven’t had a checkup in a long time. He does not weigh me or measure my height. He has the nurse take some blood. I feel cared for, neither too much nor too little. There is a copay, though not a large one, and the doctor takes that with a credit card machine he keeps in his office.

I went to acupuncture a couple times in the last weeks too, because I could. I asked the acupuncturist to help me learn Norwegian and after the first sentence I had no idea what he was saying. He told me I should go work in a preschool because the kids would help me learn the language. The following week he said the same sentence again and though I recognized it, I was too startled to comprehend. Behandlingen jobber på kroppen din: the treatment is helping your body.

Invisible buttons pressed. Pictures unseen but felt.

The water rushes downriver and flings itself wildly over the artificial barriers meant to steer fish in one direction, logs the other. Bursting waves pitch themselves headlong towards the sea.

At the library last week, the tables were full with people from around the world. Beginner level, I am seated with a woman from Guatemala and a woman from southern Ukraine. The Ukranian woman is 60. Her husband is still there. Her kids are in Germany and Italy. I am trained as engineer. Now as she says, I cannot find a job. Now my job is: I learn Norwegian. I offer a couple words in my mashup of Slavic languages to try to help her and she responds with a flow of Ukranian explanation I do not understand.

The woman from Guatemala is a classically trained violinist. We stumble through the present tense: I ask who her favorite composers are. Bach, Mozart, and, yes, yes, Schoenberg. Schoenberg! I raise my hands and gesticulate with prelinguistic enthusiasm. She wants to work. She is a music teacher. Over the two hours we laugh a lot together with the language trainer, an older woman who volunteers with the Red Cross Norwegian Language Training sessions. When two hours of conversation are up everyone is tired. We pack up and leave without further chit-chat.

Yesterday I saw the Ukranian woman at a different library session but I am placed instead in a group with a woman from India, one from Colombia, a man from Ethiopia and a retired man who is also a volunteer Red Cross Norwegian Language Trainer. I struggle to keep up and scribble vocabulary in notebooks that also contain notes about things I’ve read, conversations and meetings, exhibition venues, and scrappy storyboards for video installations.

I learn the word for sky is himmeln and the word for cloud is sky. The sky is in the heavens. My letters to you are answered but the answers are incomprehensible to me.

On the wall behind where I write here in the studio are printouts of the CAD drawings that two years ago I was convinced would be the key to the next phase of my project, things to have made instead of making myself: glass sculptures of a hollow earth, a balloon anchor, and an hourglass filled with steel grit, the ballast used these days to move a stratospheric balloon vertically. Last year, my contact Kai, sales manager at the scientific glass company in Colorado, with whom I had had hours of conversation, ended up having way too much workload and no more time to respond. After some months I moved on from trying to get him to do it but he sent me the CAD drawings they might be useful to you in the future. Or they are scraps, parts of process, bits of ballast. To shed, drop, let go, means to loose gravitational bonds. For a time.

Notebooks hide in drawers all over the studio. By night, or when I’m not paying attention, they copy their ideas over into each other. Sometimes I visit them and find they agreed on things long ago that I eventually got around to doing. Variations.

In one notebook I find diagonal lines scrawled in my handwriting about a casual conversation I recall with great affection. It took place a year ago, while filming in the hallway of the Esrange Space Center in Sweden, between the cafeteria and the recreation room. I’m sure I have written about this before. I will keep it in the present tense in keeping with my current language learning level.

I am standing filming the hallway, waiting for people to come in and out. A man walks in and I say hello and he asks what are you doing here and I say filming the BEXUS student stratospheric balloon launches. He is a rocket scientist from India. I ask him a lot of questions about why here and what he does and so on and he answers me with generosity and patience.

At one point the rocket scientist mentions that low orbiting satellites require occasional external pushes to keep them from falling back to earth. And that rocket scientists have to make those pushes happen remotely. But gravity eventually wins out, which is why at a certain point orbiting objects or anything not fully out of earth’s pull will come back. Even if the objects are orbiting for years they have to have a little shove to stay in circulation. This is physics and I take it as a metaphor which is why I write it in the notebook and put it here again too.

A year later, that is, just three weeks ago, at the Technical Museum in Oslo where O wanted to visit and I had never been:

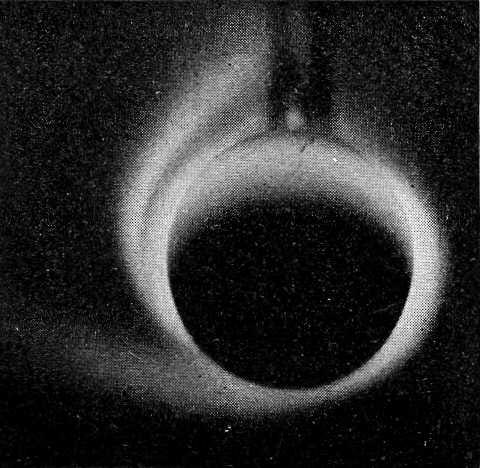

Few people are walking around in the historical section. It is filled with technologies from centuries past and isn’t particularly well-designed. I look down into a vitrine and my eyes shift from scanning to a devotional gaze. There lie scraps of Birkeland’s terella. If you shoot electricity at a big round piece of iron, you can produce miniature auroras at both poles. Birkeland didn’t invent this, but his is important, especially for Norway. On the wall a sign says that two rooms from where I am standing there’s a working replica of Birkeland’s terella you can activate. Gleeful, I skip over to the enormous box and press the big button on its front.

The inert gray iron sphere suspended in the glass box receives a beam from the far corner. After a fraction of a second’s buzz, two glowing pink electric circles appear over each end of the metal model Earth. Then the beam stops and the pink electric circles vanish. I press the button again and produce a new momentary glow. My excitement expands. Other visitors come by and I show them how to press the button. Alight, I depart.

Thanks for reading.

I had the pleasure of talking about BUNKER at the Royal Geographical Society’s annual conference in London last week, where I was invited to present on a panel called Speculating on/with the Subsurface, as part of the Thinking Deep research group, led by Professor Harriet Hawkins in the Centre for the GeoHumanities and Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London.

You can see BUNKER on streaming platforms such as Mubi, Metrograph, Amazon and Projectr.tv.