Verisimilitude, n.

The quality of seeming true or of having the appearance of being real. (Cambridge)

One of the good things about being an artist is the license. I have no responsibility to be accurate and I can smash things together as I see fit by using the explanation of that mysterious and illegible word imagination.

In times like these, imagination serves me well. I’m sure I have written here about my slow reading of Scott Sandage’s brilliant book Born Losers: A History of Failure in America which treats the shift of understanding of the term “failure” from an economic or business-related collective experience to an individual horror as it is experienced in this pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps pseudo-meritocracy that the United States claims to be. Sandage’s book also describes in detail the rise of the credit system in the U.S. and the banking collapses and economic crises that demolished lives across the country as its lands were being increased by vast land grabs and ethnic cleansing of indigenous populations.

Both reading facts and using imagination have been useful for me lately in thinking about Poe, balloons, and Andrew Jackson, military general and later president whose many violent wars and territorial expansions added millions of acres to the United States holdings. Bank failures in 1819 and 1837, threats of secession and wars before and in between all featured in these years encompassing Poe’s short life.

I recently read a 2009 essay from the New Yorker by the American historian Jill Lepore reviewing some books about Poe that were published for the 200th anniversary of his birth. The essay discusses Poe’s magazine writings and I was pleased to see that much of what she wrote aligned with my non-scholarly imaginative ways of thinking and working.

Poe’s poverty, feelings of abandonment and genuine economic desperation together with his brilliance all were factors in the speed at which he wrote and in his practical turn from (failed) novel to quicker, slightly more profitable short story. His writings are filled with fast-paced turns from abandonment, resentment, and anger to measured and calculated description.

In life, Poe made stuff up, behaved petulantly, wrote scathing, sarcastic criticism, and loved people, knowledge, and good writing. Maturing in a time when what was called science was shifting from a gentlemanly pursuit to a specialized focus (the word “scientist” was first used in the 1830s), and when the explosion of tabloids and print media spread every manner of explanation far and wide, Poe’s play with and devotion to language around science, logic, and speculation toyed with readers’ expectations.

I think about the pleasure and far-flung carelessness with which Poe wrote The Unparalleled Adventure of one Hans Pfall (1835). The story is enveloped as a letter with a double-parenthetical narrative structure. That is, we have a narrator telling a story about reading a letter sent by Pfall via a messenger from the moon to earth.

But the story doesn’t stick to the form of a letter. Diary, notebook, compendium, and ledger are all stuffed in there, and it ends so stupidly, with a big old cranky snark at anyone who claims to be a figure of authority or expert. The story is a messy patchwork and it just goes. When you’re done reading Pfall you’re not quite sure what you read and, rereading it, nothing “fills in.” Blank spots keep appearing.

I like exploring works that are considered an author’s “second best” or non-masterpiece. I like to think about what the artist is trying to work out. The imperfect lets me in. I am not fully transported but instead find myself in stops and starts, dead-ends or sharp angles, the feeling of co-driving with a ghost, like being in bumper-cars where the steering wheel doesn’t turn you the way you want exactly, you jerk forward and backwards, the sparks from the metal grate above shower in different directions and you spin around without intention.

In working on this project, I have felt for some time that there is something missing. I dread the feeling that the work has to be comprehensive but also worried I am taking the easy way out by throwing together pieces I can fog up with my own words, something that won’t actually communicate on its own without elaborate gesticulations, narratives of contextual information.

What I want to do is write it out. Right now I am wanting to make some joins with Andrew Jackson and the clearing of Indians from the American continent in the early 19th century and the ascent of Poe’s balloon story at the same time. Of course the project is autobiographical for me too. I mean who doesn’t want to float out of here and see their creditors blow up in a ball of flame, but I also believe it is not by chance that the balloon fad in the U.S. coincided with the clearing of indigenous people from lands then overtaken by slave-holding plantation magnates and white homesteaders.

Reading General Andrew Jackson writing post facto to justify his actions in the Seminole Wars in Florida, it sounds similar to today. Jackson writes about the imperative of violence to keep the (then) Southern border safe from attack by uncontrollable elements, whether they be Indians or British or Spanish or fugitive enslaved people. Jackson describes his actions in a paranoid mixture of conspiracy, alliances of convenience, and rapacious desire. The Seminole wars lasted the entire first half of the 19th century in America. These wars began shortly after the War of 1812. I learned nearly nothing about either of these in school.

In the early 1800s, fugitives from enslavement had already been living in Florida for years, farming in tandem with indigenous people. The Spaniards, who had occupied Florida since the 1500s, supposedly mostly left them alone. The British mostly too, for their own reasons. Across the border to the north, white slaveholders were enraged at the communities living relatively freely south of the border. They declared border emergencies. General Andrew Jackson headed down to Florida, raiding forts and executing fugitives, indigenous people, and British.

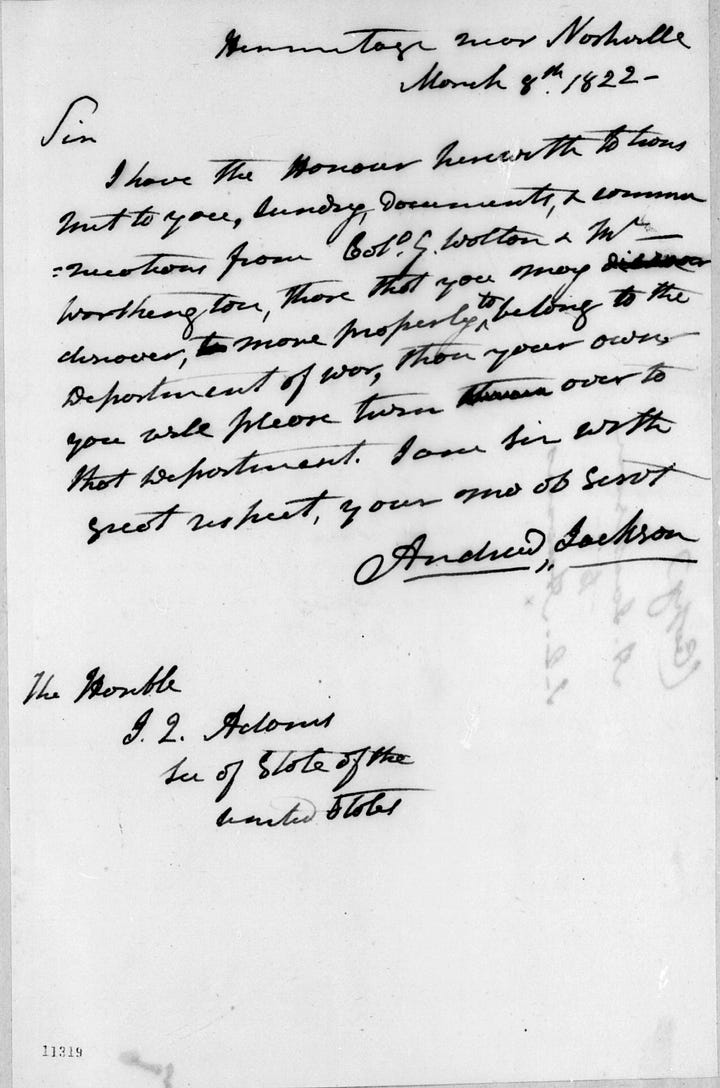

Without explicit permission from the U. S. government, the General moved quickly through the territory, taking all of Florida for the United States and forcing a treaty. In his raids, Jackson stole papers, possessions, and arms from the Spanish and refused to give them back. In 1822 Jackson writes Secretary of State John Quincy Adams from Nashville that the stuff belongs to his department, the Department of War, not the Department of State. Adams’ small, measured handwriting stands in contrast to Jackson’s as Adams requests clarification about the Spanish possessions. Adams writes that the treaty, while not totally clear, says that the Spanish stuff should probably be sent, along with the Spanish themselves, to Havana.

In 1824, Secretary of State Adams becomes president and instates high tariffs on European goods ostensibly to support Northern industry, to the fury of Southern white plantation owners. In 1828, South Carolina native, Tennessee landowner, enslaver, and populist hero Andrew Jackson defeats the one-term Adams and begins the Indian Removal policy in the United States.

Balloons allow escape from wars, bank failures, from poverty, from misery, from fake news (see the early 19th century proliferation of print tabloids, newspapers, and other publications). And scientific technologies like telescopes and balloons allow for a looking up and out into times that are not your own, future time, speculative time, imaginative time. A telescope can block out everything except what you are trying to look for, something you believe or hope is there. A balloon opens the horizon; upends scale and orientation; a telescope narrows perspective, brings the distant closer.

I read an article I should have read a while ago about early opinions about where Poe got his ideas for Pfall. The article describes the scholars’ unreliable memories and mistaken attributions. These fogs and mists wrap around the origin of the tale similar to the way that Lepore describes Poe’s own ways of inventing, inflating, deflecting, and lying about his own writings and accomplishments.

One thing stood out to me in the 1970 article by William H. Gravely, Jr. entitled “A Note on the Composition of Poe’s ‘Hans Pfaal.’” The text is mostly a discussion of whether something could have been true or not in someone’s memory of something Poe said about this minor story he wrote. A game of academic telephone, as far as I can tell.

First, the article says that in 1833 the famous American aeronaut Charles Durant launched in a balloon from Baltimore which is where Poe was living. But what I like best in this piece is that apparently Poe wanted to write Pfall because he may have read or heard about Sir John F. W. Herschel’s Treatise on Astronomy (I can go into my own fascination with Herschel & co. a later, or not at all) and how Poe wanted to write about what the moon would look like if you looked through a giant telescope that could see all the way there.

What I love about this is there needed to be an instrument that allowed the distant to be brought close. But because Poe understood that building a telescope with such powerful optics would have been impossible in order to achieve the desired narrative detail, he instead worked his knowledge of Herschel’s Astronomy into a tale of utter impossibility. Of imagination.

Instead of seeing the moon through the telescope and describing it from a position on earth, Poe sent his man there in a balloon. Which is scientifically impossible. But the science is the journey. And the story is the impossible. And that feels significant to my project. The important thing here is Poe’s insistence that verisimilitude is what makes the impossible possible. He applies scientific principles to the imagination and this becomes the story. It is hoax and not-hoax.

Thanks for reading.

In other news, BUNKER is streaming on a wide range of platforms, like Amaz*n, Mubi, Projectr, and Metrograph.